I became a secret book collector while reading about lives I’d never live.

It was about five years into my multiple-life-term prison sentence when I started. I knew I shouldn’t have. But I had to. After all, what were they going to do to me, throw me in jail?

The first time, I was nervous, excited, and committed to doing it. It was 2004 and I was at Calipatria State Prison, a maximum security prison in Southern California, where the desert wind blew hot and dry. I sat in my dim-lit cell staring out through the holes of a steel door that resembled a huge cheese grater. I was concentrating so hard I could hear my own heartbeat in my ears. I waited for the corrections officer’s footsteps to fade into the distance and the shadows to stop at another cell. I didn’t want to be seen. Not that it mattered. I had to have her. I had fallen in love and nothing was going to stop me from taking her with me.

On the outside she was…aged. A tattered paperback with yellowish and soft delicate edges. I could smell a faint mildewy scent of antiquity emitting from her ink-printed surface. I held her spine and opened up Ovid’s “Metamorphoses” to Book X, Pygmalion and Galatea’s tale. I couldn’t risk leaving her behind. I had been exposed to a pure, uncompromising love. Pygmalion had demonstrated commitment, discipline and self-control for the ideal mate. So, I broke open a razor and spent a few minutes every hour scraping off the big red letters Property of Calipatria State Prison Library from the binding of the book.

Today, Pygmalion’s story might be considered misogynist. I found it to be quite the opposite, romantic and empowering. Pygmalion, a sculptor king obsessed with perfection, wouldn’t marry because he had handcrafted the ideal partner for himself. Somehow I felt Pygmalion’s pain as he tried to bring perfection into an imperfect world.

In my younger years I had felt the loss of an elementary school crush that outgrew me and friends that changed circles and drifted farther from me. In that sense of hopelessness, I understood his longing for the perfect partner, friend and relationship. There were days when I felt his hurt as he kissed his masterpiece with no reciprocation. And then one day my heart leapt when Venus gave life to Pygmalion’s statue. My eyes moistened for the first time in a long time, when the statue, Galatea, kissed him back.

There was something special about a couple that came together in private because one of them wanted the other to be the best that she could be and that he could have. It was as if his vision of her brought the best out of the raw ivory he had chiseled.

No one will be surprised that I took Fyodor Dostoevsky’s “Crime and Punishment” in 2006. The dark cover and red lettering had caught my eye. Crime screamed out at me and punishment whispered in my ear.

By 17, juvenile hall had made me an avid reader. Time stands still while you’re in limbo, that phase of incarceration between the arrest and the day you get sentenced. So you start to live in a different world. I was housed in a maximum security unit in Orange, California, reserved for juveniles facing life sentences for violent crimes. We were separated by thick walls and solid iron doors. The only noise and light from the outside crept in through the bottom of the cell door.

We were allowed out an hour a day, alone, so books became my companions. I started with “Chicken Soup for the Teenage Soul,” “Chicken Soup for the Old Soul,” “Chicken Soup for the Single Soul” and I swear it must’ve been chicken soup for the lost soul. I read everything I could find on a dingy little bookshelf in the dayroom, which I passed on my way to the shower.

Later I became infatuated with characters that resembled me. No one will be surprised that I took Fyodor Dostoevsky’s “Crime and Punishment” in 2006. The dark cover and red lettering had caught my eye. Crime screamed out at me and punishment whispered in my ear.

“Hooked on Phonics” hadn’t prepared me to pronounce Raskolnikov, so I called him Rascal. I was captivated by his quandary. A young impoverished law student committing a brutal murder out of desperation, anger and delirium. I knew many rascals in prison. High Desert State Prison held a rascal who had robbed a liquor store for a carton of cigarettes and a bottle of Mad Dog 20/20. Another at Ironwood had run two people over for giving him the bird while crossing in the crosswalk. I often wondered if these rascals ever had the internal musing that Raskolnikov fought in his bouts of delirium. I certainly felt like everyone knew what I had done. I was even paranoid when I scraped off Property of Ironwood State Prison Library.

In 2006, I encountered an irresistibly thick novel, Leo Tolstoy’s “Anna Karenina.” Anna was full of passion, desire and the need for adventure. Her inclination to make decisions for all the right reasons—love, belonging and adventure in spite of the risks involved—mesmerized me. She reminded me of a younger version of myself. I anxiously read ahead, even to the point of falling asleep midway through a page, desperate to see how she and her lover would be happily ever after. And then she got pregnant. It was painful when she gave into suicide.

I had felt the same sense of despair and had attempted to escape my own reality more than once. But unlike Anna, my destiny was the result of bad choices for wrong reasons. While I scraped the Property of High Desert State Prison off, the binding of the almost 1000-page novel, I thought about the weight Anne carried with her.

I was transferred often for administrative, disciplinary and security threat reasons. It happened so many times that I had to become picky with my collection. Prison administrative rules are a bit of a mystery; I could never understand why I could only have 10 books. I didn’t want a whole encyclopedia set to lug around, just enough of a library to tantalize my eyes and stimulate my mind.

Whenever I transferred, I carried the guilt of knowing I had taken a piece of priceless treasure with me. I’d quietly stand in line in my white paper jumpsuit waiting for the transportation team to handcuff, shackle and chain me up for each bus ride. But my mind raced, preoccupied with the books in my property boxes. My eyes darted to catch a glimpse of the apple boxes labeled with my name. I knew which one had my books. The corrections officers at Receiving and Release would double check our property to make sure we didn’t exceed the limit of items. They always placed my books in the boxes with the thickest bottoms. Once they were loaded I could relax.

One of the hardest parts about leaving prison was carrying out the heavy boxes of souvenirs that tethered me to every place that held me. I kept paperwork I’d never need, disciplinary infractions I want to forget, 1990s jewelry I’ll never wear. And the books I’ll never forget.

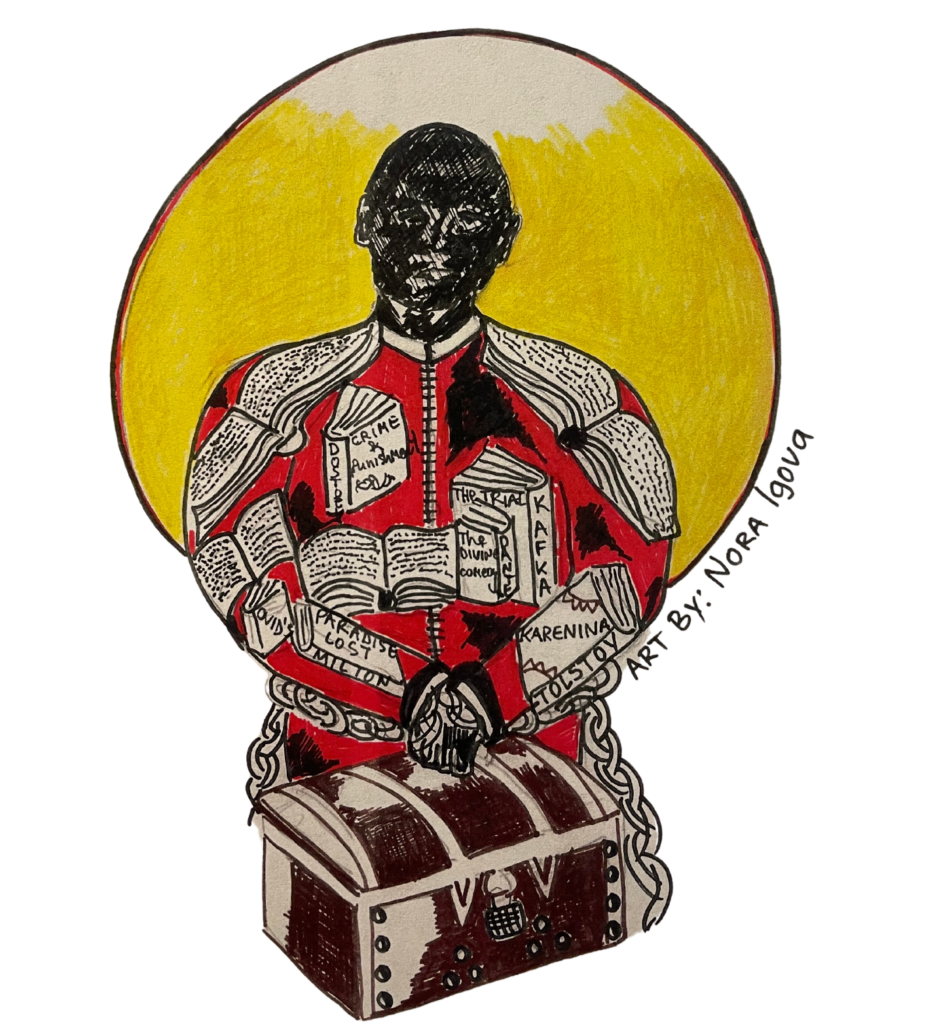

My 10 hand-selected collection contained: Ovid’s “Metamorphoses,” Dostoevsky’s “Crime and Punishment,” Tolstoy’s “Anna Karenina,” Dante Alighieri’s “The Divine Comedy,” C. S. Lewis “The Complete C. S. Lewis Signature Classics,” Machiavelli’s “The Prince, “Franz Kafka “The Trial,” Aristotle’s “Politics,” Victor Hugo’s “Les Misérables,” and John Milton’s “Paradise Lost.” I don’t know if anyone is missing them, but I didn’t want to have to live without them.

Jesse Vasquez is executive director at Pollen Initiative.

AMAZING essay!! Loved it!

Really great essay! The love of books and learning is beautifully described and inviting. One favorite line: “I never understood why I could only have ten books.” Thanks for sharing this story and this love.

Wow, Jesse, this is written so well! Your emotions of the experience really come through. Thank you for sharing with the community.

Such a great read. I have my small collection of classics on display in my living room. I feel like they are part of my history.