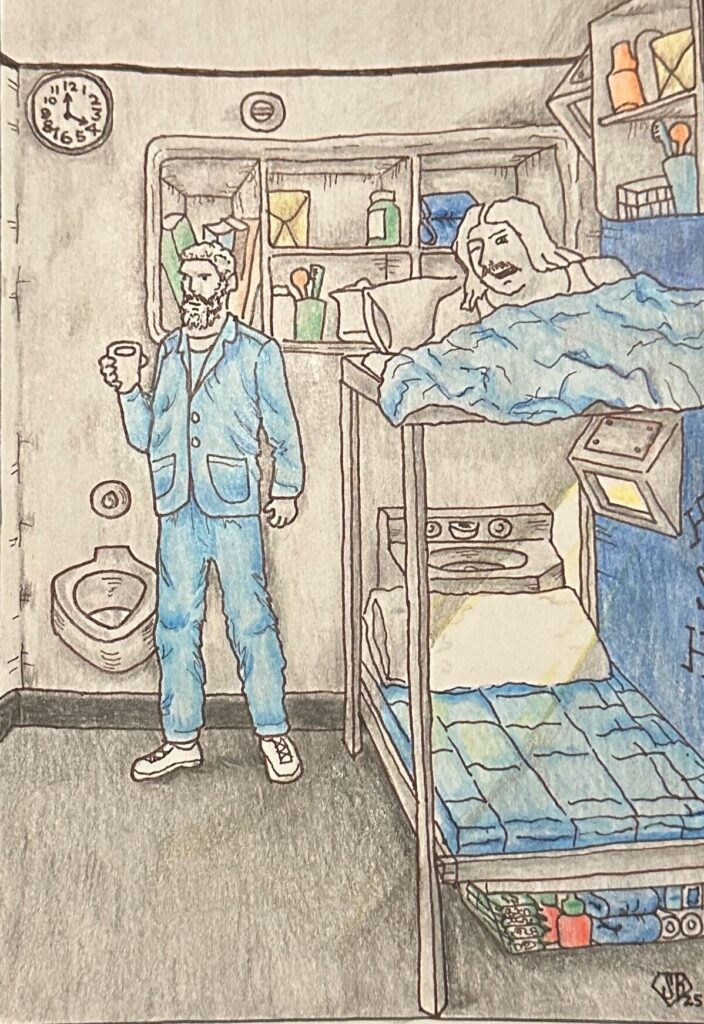

I woke up at 4:00 a.m. last Saturday morning and noticed that my cellmate “Curly” was completely dressed. That was unusual. Curly is 63 years old and has had some serious medical concerns over the past year. They took him out a couple of hours later. He knew he was going but hadn’t said anything.

That was not unusual. We don’t talk a lot about the serious issues, things like the 30 or 40 years we’ve been locked up, the chances and prospects of getting out, illnesses in the family, dead relatives, or the fear of losing somebody close. When we do talk, it’s about football, what’s for chow, or what’s on TV.

I should have known something was up. We were playing cards a few days ago, and Curly snapped about something inconsequential, some minor imagined infraction that didn’t even exist except in his own mind.

I’m not saying that’s completely without precedence, but it’s a rare occurrence. What’s even rarer is that later that night, he apologized. Now, “that” is unusual. Unusual, like getting a parole date, having a major organ removed, or seeing a unicorn. I’ve known Curly for 15 years and, in all this time, he’s never apologized to anybody about anything. He must have been alerted by medical that they were finally going to take him out for a kidney extraction.

This Level 2, medium security facility, in many ways, is more reminiscent of an old folks’ home than a prison yard. Some guys aren’t even trying to get out anymore.

Looking forward to something like that can raise the stress levels. About a year ago, we began noticing the rapid weight loss —over 60 pounds in less than three months.

Curly is over 6 feet tall and usually a steady 260 pounds. He’s got a head like an oversized bowling ball, a scraggly beard, and sort of shuffles when he walks. He can’t see very well, declared legally blind. But when the football spreads come out, he breaks out the magnifying glass and two pairs of coke-bottle glasses and studies the odds.

He finally went to the clinic to check out the weight loss. When he came back, he said they asked him if he was sleeping alright and if he had been drinking plenty of water, the usual response to illness complaints. Eventually, he was sent out for an MRI, and they discovered a tumor on his right kidney; it was cancer. Curly said it took him a few days to let it settle in, to accept it, and decide what to do. What can you do?

We’re at the mercy of a system that’s overburdened with an aging population with a vast array of medical issues, many using walkers or wheelchairs. Former gangsters and tough guys who came in in their twenties and thirties are now in their 60s and 70s and a good 20 years beyond their prime rehabilitative date.

This Level 2, medium security facility, in many ways, is more reminiscent of an old folks’ home than a prison yard. Some guys aren’t even trying to get out anymore. One 80-something former cellmate said, “Where would I go? Nobody’s going to hire me anywhere; everybody I’ve ever known out there is dead. Here, I got a place to sleep, three meals a day (of questionable edibility), and access to medical attention (of questionable reliability). Out there, I got nothing.”

What he didn’t say is that he’s got friends here. Out there, he’s got nobody.

They say when a guy comes in, his emotional growth stops the same year he was incarcerated. Curly serves as a pretty good example of that claim… as I’m sure many of us do. Like it was yesterday, he talks about seeing Lynyrd Skynyrd live a month before the plane crash that killed Ronnie Van Zant, as well as the lead guitarist and his sister, a backup singer. When he was a teenager, a buddy asked him to go on a tour with Heart and Peter Frampton. He thought the guy was full of it and didn’t go. Later he found out the guy was for real. He’s told that story more than a few times. We all listen like it’s the first telling. Friends don’t call out repeat stories. You just nod and enjoy it, thinking about what might have been.

When a guy does get a date, it is a rare occurrence. We see him waiting by the gate early in the morning with a plastic bag filled with whatever scant possessions collected over a lifetime that he deems worthy of carrying out. The gate that leads to R & R (Receiving and Release) is near the entrance to the chow hall. For the three buildings going to breakfast, for the nearly 800 prisoners passing through, 800 prisoners who are not going home, not today (for many, not ever) seeing that one who’s leaving is a unicorn sighting.

Curly got back from surgery early this week. They don’t keep prisoners too long in a hospital bed; there’s insurance and overtime for the guards who are watching them to consider. When he got back he said, “They told me to get a lot of rest and drink plenty of water.” It was meant as a joke, casting a humorous light on a dark situation. He’s been a little woozy since the operation. He fell out in the shower yesterday. This morning, he forgot my name. He won’t admit to anything other than, “I’m alright, I’ll be alright,” or mention the fact that with one kidney left, if that one goes down, things could get bad fast, or that he has doubts about any expectation other than a full recovery. That’s a unicorn sighting that will never happen.

D. Razor Babb writes from Mule Creek State Prison in Ione, California. Babb founded the Mule Creek Post in 2018 and now serves as a features writer on the incarcerated-run newspaper.